The history of ransomware spans over 30 years. The first specimen, known as the AIDS Trojan, was delivered via physical media using the postal system, and, upon its discovery, was quickly remediated by the security industry. More recent examples have proven comparatively more devastating, most notably the Colonial Pipeline incident, which caused fuel shortages and widespread disruption to much of the US East Coast.

This increasing impact is driven by a growing technological and business acumen among ransomware gangs. In addition to weaponizing vastly more sophisticated technologies and deployment methods, these gangs have undergone an organisational shift, moving from isolated cells to a franchise model. By licensing the technology to other affiliated operators, these gangs can inflict greater levels of damage and act with increasing precision and ruthlessness.

Faced with this threat, organisations must prepare for the worst, while hoping for the best. Building a viable defensive posture demands an organisational approach, with a strong technological basis at its foundation, while also recognizing the role each individual employee can play. Moreover, with ransomware attacks now including elements of public humiliation, organisations must now consider their communications strategy in the event of a breach.

We created a video that highlights some key points around the history and evolution of ransomware:

The Impact of Ransomware Attacks

This past year, a vast swath of the US east coast experienced devastating fuel shortages. This was not necessarily unusual. Americans are used to fuel breadlines in times of crisis. Shortages routinely occur in the wake of natural disasters, like hurricanes and floods, when roads become impossible to tankers. Those of an older generation might even remember the OPEC embargoes of the 1970s, when the oil producing regions of the Middle East boycotted the United States for a period of seven months.

But this was different. Rather than being caused by a freak weather event or a geopolitical meltdown, forecourts ran dry because the region’s primary fuel supplier had fallen victim to a ransomware attack.

The Colonial Pipeline is a long, arterial tube spanning from Houston, Texas, to New York City. It is the very definition of critical infrastructure and provides almost half of the gasoline to the East Coast and a significant portion of its aviation fuel. Attackers likely affiliated with the Russian cybercrime group DarkSide had penetrated its billing system, preventing any new transactions from taking place until the operators paid a $4.4 million ransom.

For the security industry, the Colonial Pipeline incident was disturbing proof of a new trend. Ransomware operators were no longer content to solely target individuals, making a few hundred thousand dollars at a time. Rather, they had shifted their focus to sensitive areas of national infrastructure, ranging from the energy and healthcare sectors, to food production. It was not always this way.

A Brief History of Ransomware

The first known specimen of ransomware dates back to 1989 with the AIDS Trojan. Written by Dr Joseph Popp, an eccentric Harvard-educated evolutionary biologist, the malware was distributed via floppy disks mailed directly to the 20,000 attendees of a World Health Organisation’s AIDS conference.

The AIDS Trojan was decidedly stealthy. Once it infected a machine, it would lie in wait and only spring into action after 90 boot cycles. At that point, it began encrypting directories and filenames, and would only reverse its damage unless the victim “bought” a license. This process involved sending $189 to a post box in Panama.

The AIDS Trojan was undeniably devastating, but its providence was in keeping with the time. Popp was not part of a cybercrime gang, raking in millions of ill-gotten funds each year. Nor was he a shadowy state-sponsored operator. Rather, he was an eccentric, much like the hackers and malware developers of the time. At his trial, Popp reportedly wore condoms on his nose and curlers in his beard. His defence hinged on the fact that he intended to use the funds raised from the malware to support AIDS research.

Fortunately for victims, the damage wrought by the AIDS Trojan proved easy to reverse. Following its analysis, a remediation program called AIDSOUT was released. Written by Virus Bulletin editorial advisor Jim Bates, this tool removed all traces of the malware from the system and decrypted the file names and directory extensions.

Ultimately, the AIDS Trojan was a failure and did not prove especially widespread or lucrative. The same cannot be said about the ransomware strains that followed.

The first real modern ransomware program dates back to May, 2005, with the release of PGPCoder. Unlike the AIDS Trojan, which was distributed through physical media, this primarily used drive-by-downloads as an attack method. Victims would visit an infected website, which would take advantage of inherent flaws within the browsers of the era, and automatically download and install the malware.

Once entrenched within a system, PGPCoder encrypted all files with a certain extension (including, but not limited to, .doc, .html, .jpg, .xls, .zip, and .rar). It would also leave ransom documents in each directory instructing the victim to pay a specific fee, between $100 and $200, to a digital money account.

As PGPCoder predated the advent of anonymous cryptocurrencies, the authors listed accounts with E-Gold and Liberty Reserve. Both services were closed by US authorities over money laundering and financial compliance concerns.

As was the case with the AIDS Trojan, it would later prove possible to remediate the damage caused by PGPCoder, as it relied upon symmetric encryption to encrypt and decrypt files. Industry experts eventually learned the encryption key used by comparing large volumes of encrypted and decrypted files. Later variants, most notably GPcode.ax, would incorporate aggressive countermeasures to defeat decryption efforts.

As time progressed, ransomware authors adopted increasingly sophisticated methods. Strains shifted from symmetric to asymmetric encryption, further frustrating efforts from the legitimate security industry to create practical decryption tools. The monetization strategy changed, too, with cryptocurrencies replacing other, more easily traceable methods.

The most notable example is the infamous Cryptolocker malware, which emerged in 2013. This strain was the first to accept Bitcoin. Although, perhaps due to the nascent stage of the cryptocurrency ecosystem at that time, it also allows victims to pay the ransom through Green Dot MoneyPak prepaid cards.

It is interesting to note that in recent years, bitcoin has lost some of its appeal to criminals, in part due to its inherent and irrevocable transparency. With all transactions permanently listed on a Blockchain ledger, authorities can trace funds to the recipient. This has led to ransomware operators increasingly favouring Monero, which obfuscates the origin and destination of transactions by design.

Later years would also see threat actors diversify their approach to distribution. Rather than relying on drive-by downloads or malware-laden emails, they would instead exploit underlying security vulnerabilities within the system itself.

The SamSam ransomware, which first emerged in 2015, did not rely on human error to proliferate. Instead, it would use known exploits in commonly found web and file servers, as well as brute force tactics. From this, researchers can infer that the authors had positioned the malware with businesses and public sector organisations in mind.

These entities are acutely susceptible to any form of disruption, and often cannot function without access to business-critical files and documents. This, in turn, means that the actors behind ransomware can demand (and often exact) more considerable sums of money. After a SamSam outbreak in 2018, the City of Atlanta faced the unenviable prospect of paying $51,000 to unlock all compromised computers. The eventual cost to the city topped $2.6 million, accounting for the disruption to services and the expense of remediating the problem.

Similarly, we can point to the WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware outbreaks in 2017, which exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft’s SMBv1 implementation dubbed Eternal Blue. This vulnerability was initially discovered by the US National Security Agency, but was not disclosed, preventing Microsoft from remediating the problem. Eternal Blue was one of the many exploits leaked by the Shadow Brokers hacker group in mid-2017.

In both instances, the intended recipients of the malware were not individual users, but rather large institutions. WannaCry affected computers used by the UK’s NHS, Spain’s Telefonica, and car production facilities operated by Nissan and Renault. It also contained a ransom note translated into over twenty languages, including English, Russian, Spanish, Turkish, and Korean. Subsequent analysis of the note suggests it was written by a Chinese speaker, with many of the translations performed by the Google Translate service.

NotPetya, meanwhile, primarily affected large public and private sector institutions in the Ukraine, although smaller outbreaks were recorded in other countries, including the UK, US, and Germany. Victims include Kyiv Boryspil International Airport, Ukrainian Railways, and the State Savings Bank of Ukraine.

The Shifting Ransomware Business Model

The first generation of ransomware did not care what computers it infected. It made no distinction between individual users, who may be inclined to simply cut their losses and perform a fresh install of windows, and larger business and government entities that could be coerced into paying a ransom.

Early variants, like the aforementioned CryptoLocker and PGPcoder strains, would encrypt immediately upon execution. This approach, admittedly, did have its advantages. By focusing on volume, the odds of finding a victim willing to pay the ransom increase. However, it does foreclose on any opportunity to take into account the victim’s means of paying, as well as the relative value of any data encrypted.

The second generation took a different approach. Strains weaponized vulnerabilities in the kinds of software used within organisations and included measures that would allow them to move horizontally throughout the network. Infections would not be contained to just one workstation. In the case of WannaCry, which spread throughout hospitals in the UK during 2017, it affected the administrative computers used by doctors and nurses and embedded systems found within medical appliances.

This approach aims to maximize the amount of disruption, ostensibly to incentivize victims to pay the ransom swiftly. It also allows threat actors to demand larger sums of money than would otherwise be feasible with individuals. This is demonstrated by recent payouts, including one from American travel services company CWT Global, which paid $4.5 million in Bitcoin to the operatives of the Ragnar Locker malware. Colonial Pipeline paid a similar figure, $4.4 million, although law enforcement eventually recovered these funds from the recipient wallet.

And finally, we arrive at the latest generation, with ransomware operators adopting a franchise model almost akin to a fast-food restaurant chain, like McDonald’s.

The most notable example is REvil. Its business model relies on the recruitment of operatives to distribute the ransomware on its behalf, with the parent company taking a portion of all revenue. This approach allows a malicious actor to rapidly scale its efforts, resulting in a greater number of organisations targeted and a growing name-brand recognition.

This evolution has coincided with another troubling trend, with ransomware gangs weaponizing the data captured during incursions. One approach designed to increase the likelihood that a victim will pay a ransom is to leak confidential data. The REvil group is notorious for this, and will routinely publish stolen proprietary information on its “Happy Blog.”

In April of this year, the gang targeted Quanta Computer, a large Taiwanese ODM firm specializing in consumer electronics and PCs. The company’s list of clients includes well-known tech giants, such as Apple and HP. After Quanta and Apple refused to pay the gang, it responded by publishing blueprints for yet-unreleased MacBooks.

It is important to note that REvil has also threatened to use this tactic against high value individuals, including singers Lady Gaga and Madonna and former US President Donald Trump. Although the group did not follow through with its threats against Trump and Madonna, it did leak 2.4 GB of legal documents belonging to Lady Gaga.

Although an organisation may dread the thought of their proprietary information becoming public, they may fear a public relations backlash even more. This sensitivity is increasingly weaponized by malicious actors, most notably by the MAZE ransomware group, which publishes the details of entities that fail to pay up on its “name and shame” page. In another instance, a ransomware group infected the systems of a plastic surgery centre and subsequently threatened to reveal the names of its patients in the case of nonpayment.

Ransomware groups may also opt to use the stolen data as a commodity rather than a bargaining chip. Malicious actors have listed stolen data on dark web auction sites, harvested credentials from dumps to be sold separately, and weaponized their hauls in the commissioning of spear-phishing attacks against the organisation’s external partners.

Evolution, Not Revolution

If one was forced to summarise the evolutionary shift in the distribution and targeting of ransomware in a single word, it would be “professionalisation.” The first strains were decidedly ad-hoc, delivered imprecisely and reliant on user error. A victim would have to visit an infected website or willingly open a malicious email attachment. Decryption fees were flat and universal, and the encryption methods used were unsophisticated and easily reversible.

Now, it is a business. Consumers are not the target, but rather public and private entities. Ransomware gangs use increasingly exotic methods to deliver their payloads, even using leaked exploits taken from the heart of the American intelligence apparatus. Ransoms are larger, although there is evidence of an almost transactional relationship, with some gangs willing to barter with their victims to reach a mutually agreeable price.

Furthermore, like many businesses, many ransomware gangs have undeniable growth ambitions, demonstrated by the adoption of a franchise business model, which is often referred to as ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS).

This trend is part of a natural evolution. As gangs become more experienced, they will adjust their tactics and methodologies. Over two decades, they have learned which targets are most likely to pay out, and what data is worth stealing.

The threat actors of 2021 are not individuals like Dr Joseph Popp, motivated by idealist notions or personal levels of avarice. They are ruthless, expansionist gangs, staffed by hardened veterans of the digital underworld. And now, they demonstrate the business acumen of a Harvard MBA graduate, showing the same enthusiasm for scalability and exponential growth as any Silicon Valley start-up CEO.

Ransomware is the Symptom, not the Cause

Ransomware alone is not the problem. It is merely a tool. Understanding this is the difference between falling victim to an attack and keeping any would-be attackers outside the perimeter.

And, as with any problem, the best way to find a solution is to look at the root cause. Only by understanding how an adversary could obtain privileges within a network and remain undetected while doing so can you start to build a robust defensive posture.

The best place to start for organisations is within their own incident logs. A historical analysis of events and incidents can shine a light on where issues are more likely to occur. In most cases, these will boil down to a handful of key attack vectors.

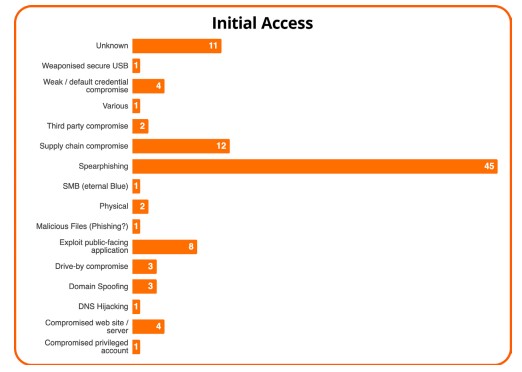

This reality is illustrated by an analysis of 100 threat intelligence reports that illustrate attackers’ disproportionate preference for social-based tactics. Spear phishing accounted for 45 percent of the incidents recorded. Domain spoofing, DNS hijacking, and physical attacks accounted for a further six percent.

Source: Using Threat Intelligence to Build Data-Driven Defence

By preventing the most commonly exploited attack vectors such as social engineering, weak passwords, or unpatched public-facing software, organisations can be much better placed to defend not just against ransomware, but a broad range of cyber attacks.

Addressing all parts of the ecosystem will allow organisations to weather both novel attacks and those utilizing tried and tested techniques. For each SamSam, which used purely technological means for distribution, countless others rely on basic social engineering and phishing tactics.

By definition, this entails looking at the monitoring and intrusion detection technologies used within a network, and identifying areas where they may be inadequate or otherwise wholly absent.

Additionally, it requires organisations to recognize the diverse approaches malicious actors, criminals, and state-sponsored entities use when distributing ransomware. In practice, this means looking at the low-hanging and high-hanging fruit.

On a fundamental level, organisations must practise good security hygiene, ensuring that all systems are running the most current version of the operating system and all associated applications and libraries. Updates must be performed at a swift and regular cadence, limiting the time opportunity for an attacker to exploit.

Expanding further, it is vital to incorporate threat intelligence, threat detection, and early warning technologies into any posture. The use of an IDS system can stop an attack in its earliest moments, potentially limiting the damage caused. Honeypots can serve as an indicator of potential interest in the network by a malicious operator.

Should an organisation fall victim to a successful ransomware attack, having a continuity plan can reduce any downtime. Any strategy should include the routine encryption of all virtual machines and online backups, paired with regular offline backups. Cyber security insurance can lessen the financial impact, with some providers even willing to make ransom payouts where appropriate.

Finally, it is essential to recognize the highly public nature of modern enterprise ransomware infections, with attackers willing to publicly shame their victims, as well as leak confidential or proprietary information.

As part of any preparations, IT leaders should consider how the organisation will approach the public relations aspect, taking into account interactions with the media and customers. This strategy should include whether the organisation intends to pay any ransom, and how it will inform stakeholders about business continuity and recovery efforts.

If an organisation creates a vacuum of silence, that vacuum will inevitably be filled with damaging speculation and innuendo, with lasting consequences.

Ransomware Prevention

Much of the discourse surrounding ransomware focuses on the immediate consequences to organisations. This is especially true if, as in the case of the Colonial Pipeline and JBS Foods incidents, the wider public becomes ensnared as collateral damage. In these scenarios, the impact is evident just by looking at the long lines snaking from gas stations or empty supermarket shelves.

It is more helpful to look at the operators behind ransomware attacks and what makes them so successful. Today’s ransomware gangs are experienced, emboldened, and most of all, ambitious. Combating this will require a holistic approach to organisational security. It is not enough to have a robust perimeter.

Any posture should include disaster prevention and disaster recovery plans, while also recognizing the human element. We have several resources available that cover ransomware even more in-depth, including a hostage rescue manual and on-demand webinars on nuclear ransomware 3.0 and a master class on ransomware. I highly encourage looking through these resources after you read this blog to understand the true impact ransomware can bring to your organization.

And, because ransomware attacks are almost always public, leaders should take time to consider a communications strategy. Knowing how they will communicate with stakeholders — ranging from customers and external partners to the media — may limit the amount of confusion and outrage that follows.

Free Ransomware Simulator Tool

Threat actors are constantly coming out with new strains to evade detection. Is your network effective in blocking all of them when employees fall for social engineering attacks?

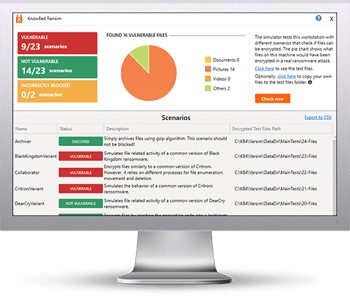

KnowBe4’s “RanSim” gives you a quick look at the effectiveness of your existing network protection. RanSim will simulate 22 ransomware infection scenarios and 1 cryptomining infection scenario and show you if a workstation is vulnerable.

Here’s how it works:

- 100% harmless simulation of real ransomware and cryptomining infections

- Does not use any of your own files

- Tests 23 types of infection scenarios

- Just download the install and run it

- Results in a few minutes!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: JAVVAD MALIK

Javvad Malik is the Lead Security Awareness Advocate at KnowBe4 and is based in London. Malik is an IT security professional with over 20 years of experience as an IT security administrator, consultant, industry analyst and security advocate. He is also a multi-award winner and is currently a Guinness World Records holder for the most views of a cybersecurity lesson on YouTube in 24 hours.

Stygian Cyber Security can help you secure your organisation against threats, ensure compliance and provide you with peace of mind with our range of cyber security solutions.

We’re a friendly and knowledgeable team, so have a browse or give us a call –we’re ready when you are.